The Etymology of Marshall McLuhan’s “The Medium is the Message”

I like to focus on what’s practical today from McLuhan work, but that said, history is important and it can be instructive and useful to know where things come from. It can also be interesting, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Some years ago, when I undertook the inventory and evaluation of Marshall McLuhan’s “working library” of some six thousand items, I made a discovery which, at the time, made me a bit giddy with excitement. I found a note, written by Marshall, showing where and when and why he first said “the medium is the message.”

The penciled note reads: “1st used this phrase in June (?) 1958 at Radio broadcasters conference in Vancouver. Was reassuring them that TV could not end radio.”1 Finding that note in 2011 was a pretty cool moment. It wasn’t a lot of information, and the question mark raised questions, but still… pretty cool. I made a post about it on the blog I was keeping at the time chronicling my inventory adventures: inscriptorium.

I did a bit of research to try to find out a date of the “radio broadcaster’s conference” mentioned, but no luck. Given my more recent discovery, I may try again to find out. The recent discovery happened in a folder marked “1975” in the metal filing cabinet containing our McLuhan archives. Started by my father Eric, we try to have a copy of everything written by Marshall McLuhan to match the bibliography-in-progress making note of same. I refer to the bibliography a lot, and hope to someday make it shareable but much work needs to be done first to make it completely accurate and presentable. I was looking for something else (to do with Laws of Media: The New Science) when I noticed another mention of where “the medium is the message” came from. This gave the date as 1957, not 1958, but more importantly, it gave more detail to illustrate the reference:

Professor Marshall McLuhan’s talk at Georgia State University on February 20, 1975. “To be published in Franklin Foundation Lecture Series publication.” Cover page / page 1.

I will spare you the customary (and quite dated) opening jokes and skip ahead to the reference in question. It’s an 11 page transcript, purportedly to be published, but I have only the transcript and there’s no mention elsewhere in the bibliography of its publication. I did a light internet search without further results.

Here’s the goods:

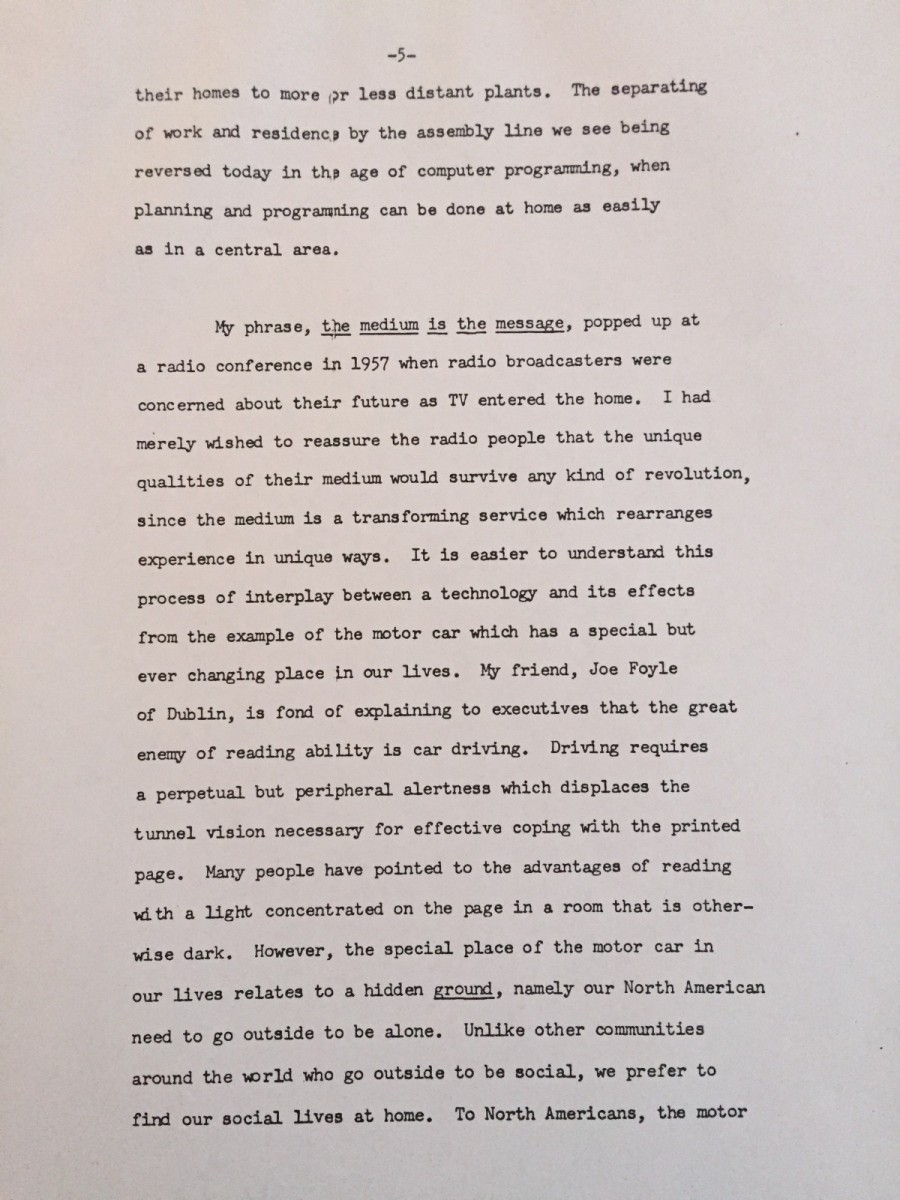

Page 5 of McLuhan’s 1975 speech at Georgia State University.

My phrase ‘the medium is the message’ popped up at a radio conference in 1957 when radio broadcasters were concerned about their future as TV entered the home. I had merely wished to reassure the radio people that the unique qualities of their medium would survive any kind of revolution, since the medium is a transforming service which rearranges experiences in unique ways. It is easier to understand this process of interplay between a technology and its effects from the example of the motor car which has a special but ever changing place in our lives. My friend, Joe Foyle of Dublin, is find of explaining to executives that the great enemy of reading ability is car driving. Driving requires a perceptual but peripheral alertness which displaces the tunnel vision necessary for effective coping with the printed page. Many people have pointed out the advantages of reading in a room that is otherwise dark. However, the special place of the motor car in our lives related to a hidden ground, namely our North American need to go outside to be alone. Unlike other communities around the world who go outside to be social, we prefer to find our social lives at home. To North Americans, the motor. . . 2

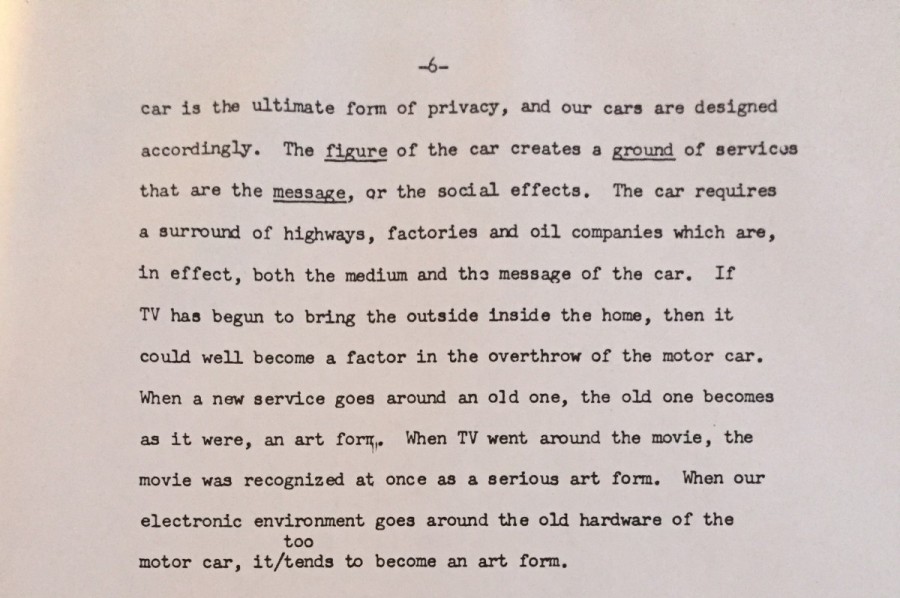

Page 6 of McLuhan’s 1975 speech at Georgia State University.

. . . car is the ultimate form of privacy, and our cars are designed accordingly. The figure of the car creates a ground of services that are the message, or the social effects. The car requires a surround of highways, factories and oil companies which are, in effect, both the medium and the message of the car. If TV has begun to bring the outside inside the home, then it could well become a factor in the overthrow of the motor car. When a new service goes around an old one, the old one becomes as it were, an art form. When TV went around the movie, the movie was recognized as a serious art form. When our electronic environment goes around the old hardware of the motor car, it too tend to become an art form.3

And there you have it. What more is there to say, really?

Of course, there’s a lot more to say. It’s McLuhan 101. Those five little words sure pack a lot into them. Fortunately, in the just over twenty more years Marshall lived, he repeated those words many times, and went to great lengths to help us understand what they mean. The first, and largest, effort to elaborate on “the medium is the message” was in that first chapter of Understanding Media,4 but he repeated it in speeches and interviews over the years. Someday I will gather them all together in one place.

Those five little words sure pack a lot into them!

Of course, what “the medium is the message” meant in 1957, with television taking over from radio, is vastly different from what it means today, with 5g and quantum computing drifting from the horizon to our hot little hands. And it will change again and again and again—which is why the statement is as true and powerful now as it was and ever will be.

“I don’t explain, I explore,” Marshall said in a 1965 interview. Let’s follow his lead.